Dionisis Christofilogiannis

Dionisis Christofilogiannis (1973)

Feels like home - Thessaloniki (White Tower),2017

Lambda on dibond 60 x 84 cm

MOMus - Museum of Contemporary Art Collections

TThe series of photographic collages by Dionysis Christofilogiannis, presents the image of a dystopian world, an unfamiliar reality. Characteristic sites of Athens (with the Parthenon, Lycabettus Hill and Omonia dominating the scene) and Thessaloniki (with its old promenade in the foreground) are combined with views of the desolate urban landscape of Syria's now-abandoned capital. These images capture and record our fragmented, irrational era, where no one feels safe, as the state of fear is bevoming entrenched and intensified by new, emerging forms of violence. We are all potential refugees, strangers among foreigners, in search of a new home, a safe haven.

Y.B.

Georgios Iakovidis

Georgios Iakovidis (1853-1932)

First Steps, 1892

Oil on canvas 140x110 cm

National Gallery - Alexandros Soutsos Museum, Ε. Koutlidis Foundation Collection

TThe First Steps is one of Iakovidis` best-known and loved works. The scene is set in a Bavarian village home interior, bathed in the light pouring through the open window. Dressed in dark cherry tones, the grandmother is holding the blond baby, full of courage and smiling, taking its first steps in the world, on top of a wooden table. The grandmother has left her red knitwear in a corner. Note this dash of red colour in Iakovidis` works; we have also seen it in his teacher, Nikephoros Lytras` paintings. The baby`s elder sister, seated with her back towards the foreground, is waiting to receive the baby with her arms open in a protective gesture. First shown at the Glaspalast exhibition in Munich in 1892, this painting marks a key change in Iakovidis` work regarding his interpretation of light. The natural light floods the scene as it comes through the window, adding vibrancy and ambiance. Note the effect of the light on figures: all white and blond, the baby is dazzling. It thus becomes the symbol of emerging new life. The incoming light, on the contrary, illuminates the girl`s outline, lining it with a bright aura. The work exudes life and elan vital.

M.L.P.

Nikolaos Gyzis

Nikolaos Gyzis (1842-1901)

Peak-a-Boo, 1882

Oil on canvas 100x75 cm

Anonymous donation in memory of D. Tzirakopoulos

Collections of National Gallery - Alexandros Soutsos Museum

One of the most important Greek artists of the ‘School of Munich’, Nikolaos Gyzis, an excellent representative of the so-called ‘academic realism’, also excelled in the field of ‘genre’ painting. Peak-a-Boo is made at a time when Gyzis, along with the rest of his work, which is beginning to show idealistic and symbolic tendencies, is also involved in the creation of portraits of familiar to him people. Here the scene takes place in a Bavarian house, but the three of the depicted persons are Gyzi's wife, Artemis, and two of their four daughters, Margarita and Penelope, while the fourth is probably a nanny. The triangular organization of the composition reflects the shape of the Gothic arch that covers it, while a lighting coming from the side window warms and enriches with reflections the fabrics and wood paneling in the background, highlighting their color quality. At the same time, it emphasizes the tenderness on the faces of the two women, as well as the form of the small child who bends down to respond to his mother's cheerful play. It is a happy family scene, with an emphasis on the atmosphere of warmth and security that the house offers as a shelter.

K.T.

Ziad Antar

Ziad Antar

Wa, 2004

Colour, with sound, duration: 3’

Donated from “The Dakis Joannou Collection”, 2017

EMST Collection

Lebanese artist Ziad Antar explores the visual languae of video with works that combine performance and music with video. In WA, the artist turns to his family environment to record –with one camera and a single frontal shot- his nephew and nieces singing along to a piece they compose on the synthesizer. The result is a playful direct and refreshing glimpse into an everyday moment that takes on the character of a minor event.

T.P.

Michel François

Michel François (1956)

The game of hands, 1990

Photograph

Variable dimensions

MOMus Collections - Museum of Contemporary Art

In his photograph The game of hands he attempts to convey - both metaphorically and emotionally - the dynamics of a beloved children's common gesture, not only as a game, but furthermore as an absolute symbol of "the strength in unity": the dynamics of the team, the touch full of confidence and enthusiasm, are elements that convey the feeling of intimacy, friendship, finally symbolizing a home that has no walls, but offers non-negotiable emotional security.

Deborah Kelly & Tina Fiveash

Deborah Kelly & Tina Fiveash

Hey Hetero!, 2001-2015

Digital photomedia

118,4 x 84,1 cm

Courtesy of the artists

MOMus Collections - Museum of Contemporary Art

Hey Hetero! returns the gaze at heterosexuality: the privileged sexuality which makes gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender movements both possible and necessary. Simulating mainstream advertisements, the artwork invites heterosexuality into public discourse.

Note: No heterosexuals were harmed in the creation of this project.

T.M.

Yiannis Pantelidis

Yiannis Pantelidis

Unknown limits (2017-2018, series of 12 photographs) - Volos 2016

MOMus Collections - Thessaloniki Museum of Photography

H.P.

To create the unpublished series Unknown limits, Yiannis Pantelidis obtained a special licence to visit eighteen prisons all across Greece, in order to study the zone separating the condition of confinement from the surrounding atmosphere. What kind of landscapes surround a prison? What kind of occupations and land uses develop around it? How is it that a rigid limit conceptualizes each single path, light opening, or muddy road around it? And how much pressure is exercised on this kind of limit from both sides, when the prison is located in an inhabited area? An open or closed gate becomes an insinuation of confinement. Similarly, the police tape, wrapped around tree trunks and crosses the frame, appears to be discreetly keeping the viewer away from the image’s field and the condition of imprisonment.

Pantelidis makes us confront limits unknown to us, since correctional facilities are usually located in the outskirts of cities or in remote parts of the countryside. They resemble heterotopias sown in the entrails of the Greek landscape, places which are unfamiliar even to those who live or work next to them. But how many more places are also unfamiliar to us? Are prison walls airtight barriers that effectively keep the worlds of freedom and confinement apart? Could it be that for many people, enchained as they are by financial, family, social and other difficulties, the division is somewhat blurred?

Dimitris Antonitsis

Dimitris Antonitsis (1966)

Family Matters!, 1998

Photographic installation

Series of 5 photographic triptychs, C-print 5 photos

50 x 75 cm and 10 photos 30 x 45 cm

Edition number 2 out of 3

Anonymous donation, 2018

EMST Collection

The aesthetic language of Dimitris Antonitsis extends from the creation of minimalist objects to a maximalist folklore aesthetics. In the series of photographs entitled Family Matters, the artist presents different family moments of transgender people and comments on the transgression through sexuality. The artist surprises the viewers by revealing themes and scenes from intense personal and family moments, about which very little is known to many outsider observers and manages to capture and reveal taboo images but also to stimulate inner emotions.

D.V.

Katerina Marouda

Katerina Marouda (1958)

Representation Νο 1, before 1984

Oil on canvas

170x120 cm

Collections of National Gallery - Alexandros Soutsos Museum

Performance No. 1 belongs to the first years of Katerina Marouda's painting, when her subject matter was exclusively anthropocentric, constituting, as she explains, ‘a study on people’s communication and relations on an axis of eroticism’.

The private element, which appears from the beginning in her work, is indicated here by three colored stripes that frame the scene, delimiting an indefinite interior space. Eroticism and death are intertwined in the fragmentarily rendered, mutilated and bloodied form of the naked woman with the voluptuous expression on the face and a head that seems to be supported by the left male hand or to be an extension of that hand.

The desperate attitude of the kneeling man hiding his face with his other hand implies the realisation of a loss in which his own involvement remains unclear. Is this a crime of passion? Τhe horrible end of an act of domestic violence? Or maybe the result of a tragic accident? The two figures are depicted with an expressionist writing, with the color intensity emphasising the violence and the emotional charge that the scene exudes.

K.T.

Alexis Akrithakis

Alexis Akrithakis (1939 - 1994)

Carousel for the children of Vietnam, 1969

Maquete 37,5 x 37,2x 21 cm

Donation of Fofi Akrithakis (2007)

MOMus Collections - Museum of Contemporary Art

The colorful work "Carousel for the children of Vietnam" (1969) by Alexis Akrithakis is a work, a revelation-protest about the "bad" war in Vietnam, for the right to life, for personal freedom and family security. The characteristic design of the artist, repeated and transformed, covers the surfaces and initially hides the sad theme that transforms from the toy-construction into a nightmare.

Akrithakis, influenced by the techniques of illustration, scenography and narration, created dense compositions with intense colors, outlines and shapes. He developed a particular style, sometimes lyrical, melancholic or sarcastic, and turned objects into symbols of escape and subversion. He dedicated series with toys, constructions, poems and short stories to his daughter. The expressiveness and narrative power, diverse and unorthodox techniques, subversive use of cheap materials and objects characterize the painter's production.

K.S.

Alexandros Georgiou

Alexandros Georgiou (1972)

Untitled (dancing in my office), 1999 (from the Cut-outs series, 1999-2001)

Photograph, C-print mounted on aluminum

50 x 75 cm

Edition 1/5

Anonymous donation, 2018

EMST Collections

The three photos from the series Cut-outs made by Alexandros Georgiou between 1999-2001, present the artist himself in different everyday home environments. As the descriptive subtitles of his works Dancing in my office state, Wrapped in scrap paper, silicone injection, Wrapped in scrap paper, cups, etc. Georgiou captures himself in different rooms of his house (office, dining room, living room, etc) as a tiny little man in a need to explore his self and his identity. The way he created these existential and autobiographical photographs reveals a strong executive dimension. The artist videotapes himself while dancing, moving, sitting and doing different postures with his body and then puts this video to play on TV and photographs the poses/scenes that interest him. He then prints them in the size of a postcard and cuts the outline of his figure so that the figure stands upright. Finally, these pop-up photos are placed in the various parts of the house, from where the final photos emerge.

D.B.

Lia Nalbantidou

Lia Nalbantidou (1967)

M/A 02-013.01, 1996-2001

From the series: The Safe Private Area of my House

Gelatin Silver Print 100 x 100 cm

Εdition 1/5 Purchase, 2001

EMST Collection

The three photographs presented by Lia Nalbantidou from the series: The safe private field of my house (in total this group includes 73 photos), depict the family context of the artist and her personal life at the given time. These black and white photographs capture the pregnant woman and identify the emotional context that is created in the new family home, during the transition from the period of girlish innocence and carelessness to this new chapter of life that concerns motherhood, married life, coexistence and family life. The photographer presents herself through the reflection of the mirror, creating an endoscopic work. The mirror has often been used in art history as a form of allegory, but as a way to look inward and struggle with complex identity ideas as well as looking.

D.V.

René Magritte

René Magritte (1898-1967)

The Healer (Le Thérapeute), 1967

Bronze

145x128x90 cm

Donated by Alexandros Iolas

Collections of National Gallery - Alexandros Soutsos Museum

The Healer is one of the eight painting themes conveyed in a 3-dimensional form by the surrealist painter René Magritte. It comes from a photograph taken by the artist himself in 1937, entitled God on the Eighth Day, and is found in a sculptural version with the cage door open, and many painted ones.

In the present version, the closed cage refers to a psychological space, where the inner self is trapped in darkness, caught in its own fears and prejudices, unable to respond to the call of freedom coming from outside. At the same time there is hope, as a dialogue is conducted with the bird from the outside world that comes to help. And one can see the hesitation but also the longing of the captured bird to respond to that voice that seems to whisper words of truth. Is it a conversation between the conscious and the subconscious part of man or a reference to a process of psychoanalysis, in which a human being opens by providing the bird-healer with a support to step on?

The absence of the head emphasizes the difficulty of man to shake off the syndromes in which he himself is trapped, as thoughts, intentions and mental processes are also caught within the cage. And the empty hat, a simple semantic trace of the head, gives in its impersonality a universal dimension to the depicted psychological state, as we all carry within us an inner self that fights with its darkness, trying to draw itself free.

K.T.

Teta Makri

Teta Makri

Untitled, 2010

Acrylic on linen

140 x 140 cm

Donated by the artist, 2017

EMST Collection

A major characteristic of Teta Makri's oeuvre, apart from its technical perfection, is an incomparable awareness of the process. Her "images" do not describe, but rather create atmospheres of magical realism which are mentally recreated by the viewer.

This way, in her painting Untitled, 2010, there is not son much a house presented, but the metaphysical search for the the idea of home (hestia), the house as a metaphor of stability, privacy and the human need of belonging. And while the ideal of home is iconographicaly presented, there is a sense of threat around it. Seems to be a memento; that everything can be overturned as the times of certainty have passed irrevocably.

Α.Μ.

Andreas Lolis

Andreas Lolis (1970)

Shelter, 2013- 2016

Marble

90 x 200 x 200 cm

Long term loan from the artist to the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens (EMST)

ΕΜSΤ Collection

In his free standing sculptures, the artist uses marble, a valuable material, and techniques of traditional sculpture to create exact replicas of objects found in the trash in today’s modern cities: packaging cardboard, polystyrene cases and wooden pallets, materials worn out or turned yellow by time. The arrangement in space of these objects, and the objects themselves, both in the Shelter and in most of the artist’s works, is an implicit reference to the improvised shelters of homeless people, and are a commentary on the marginalization and extreme consumption of our times.

A.B.

Christina Calbari

Christina Calbari (1975)

Short stories of entrapment : Counting, 2002

Photograph

MOMus Collections - Museum of Photography

In Short Stories of Entrapment Christina Calbari assumes roles that touch upon the trauma inside. Staging symbolic scenes in claustrophobic spaces, she often uses familiar objects that refer to such social institutions as family and education or social rites like marriage. By avoiding carefully to present her face in each work, she delivers a body without identity that look as if attempting to hide within the self, to deny thus the confrontation with the reasons generating this condition, allowing at the same time a meaningful generalization. The viewer attends these interior ups and downs from a secure position, without maintaining the possibility of intervention as the protagonist is, symbolically, enclosed in the surface of photographic representation.

H.P.

Thodoris Papadakis

Thodoris Papadakis

Home again, part of 6 photos, 2015

Photograph

MOMus Collections - Museum of Photography

In the works of the series Home Again (2015) Papadakis sets in public space the open cross section of an austere makeshift room, allowing its tenant to “inhabit” it temporarily as the light of the day goes out, under the discreet or indiscreet gaze of the passers-by. Combining staging with performativity, this short series of works prompts the spectator to question the diffusion of private into public and the opposite, a diffusion that rises as a key issue of our time.

H.P.

Manolis Baboussis

Manolis Baboussis (1950)

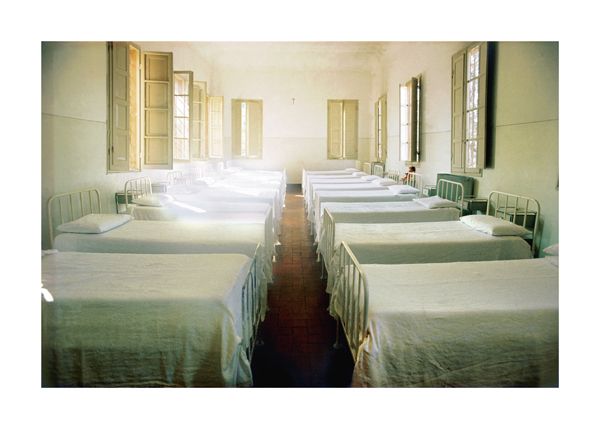

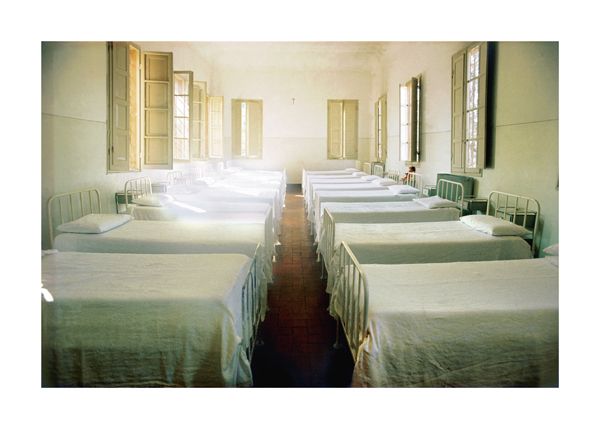

Volterra, 1973

Colour c-print

125 x 175 cm

Edition: 2/3

Purchased in 2002 on subsidy by the Ministry of Economy and Finance

ΕΜSΤ Collection

In 1973 Manolis Baboussis creats a series of photographs from the Volterra psychiatric hospital located in Tuscany, Italy. In these photographs the artist captures the architectural elements of the psychiatric hospital, the corridors, the beds of the patients, the people themselves but also their absence. This photo, entitled Volterra, shows the regularly made hospital beds with the white bed linen, presenting this sterile clinical picture with the strict and monastic arrangement of the beds, but also the very absence of people in the specific area. At the moment, the patients are elsewhere and all that we see are some of their traces as we could imagine the human presence and these fragile and tortured human beings leaning their bodies on these beds at night.

Nikephoros Lytras

Nikephoros Lytras (1832-1904)

The Dirge in Psara, before 1888

Oil on canvas

97x140 cm

Collections of National Gallery - Alexandros Soutsos Museum

The Dirge in Psara, on the theme of mourning for a sailor lost in the watery wilderness, depicts in disarming simplicity, immediacy, and truth a scene that the inhabitants of the Greek islands would experience too often. In a sparse island home interior, women and children have gathered to silently mourn the sailor lost at sea. They are seated in a circle (reminiscent of the tragic chorus) around a red fez that stands for the absent dead. The tragic figure of the father is depicted bowing, alone, in the shadowy right-hand side of the image. An impromptu iconostasis has been set up on a chair on the right. The overturned stool in the foreground stands for the absence of the dead, while at the same time accentuating the third dimension in the composition. The scene is filled with a restrained yet pervasive sense of tragedy. The painting adopts an almost monochromatic palette of browns, the only vivid colour being the red of the dead sailor’s fez. Sketching the figures in wash, in a confident, free hand, Lytras proves especially daring here. The Dirge of Psara is a major painting in the history of Greek art of the 19th century, for it not only combines authentic emotion and an extraordinary modern style but, above all, it truly reflects the life of the people, a far cry from the nostalgic, idealised, often saccharine genre paintings by Munich School artists.

M.L.P.

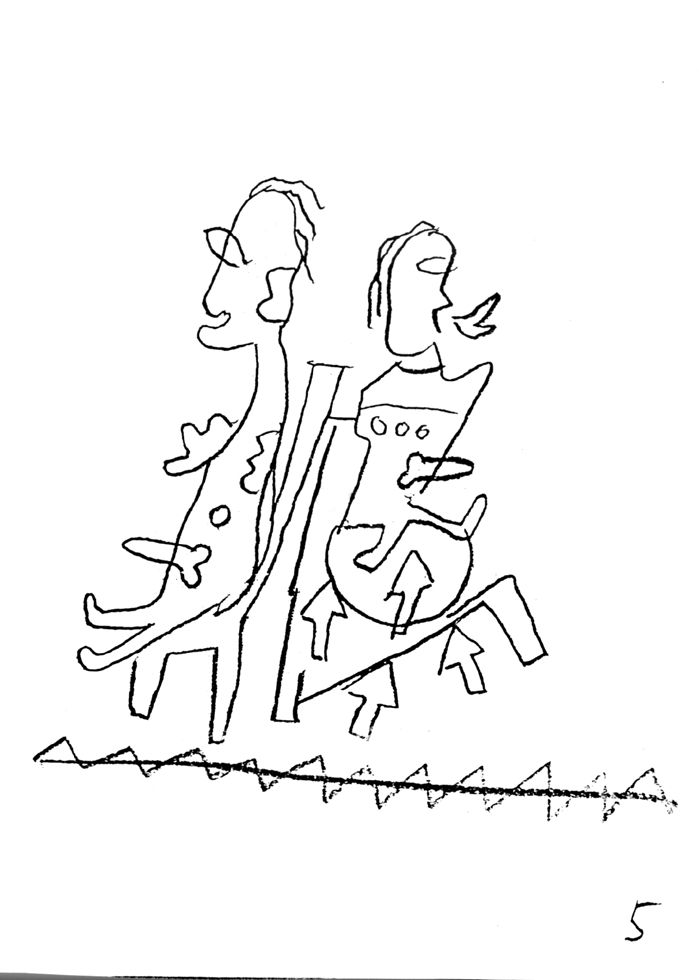

Alexis Akrithakis

Alexis Akrithakis (1939-1994)

Dromokaiteio, 1993, Series with 61 pages of the album (detail)

20x30 cm each

MOMus Collections - Museum of Contemporary Art

The Notebook of Dromokaiteio (1993) by Alexis Akrithakis contains 61 patients’ portraits of the psychiatric hospital where he was treated for detoxification. This very personal work of the artist, unfinished, is preserved in photocopies as the original was stolen from his room. The special conditions of confinement, isolation and coexistence fueled his unique creative style with expressive power. The figures are depicted with a kind of almost impulsive automatic drawing where shapes, straight and curved lines are reproduced and multiplied. The pencil drawings are a set of characters created by the artist based on his visual vocabulary with codes - symbolic references of his experiences.

The internationally established artist, authentic, self-taught, determined, daring and restless, returned to Greece with a shaken health condition in 1984. The period that followed until 1994 is the last cycle of his work. He replaced the use of oil with acrylic paints, keeping the parallel action with constructions, collage and designs, restored the works of the two dimensions and dealt with enlargements from details of older works. The process of self-knowledge, harsh self-criticism and self-sarcasm followed him throughout his life and marked his work.

As he notes (Akrithakis, 1971): “I have been painting since I was very young. I was sure that one day I would become a painter. Just like other children make stories with words, I made stories with pictures next to each other, on a piece of paper, sometimes up to four meters long. What people around me thought was art prevented them from taking me seriously, but not for the reasons that adults usually do not take a child seriously. So today there is not a single one of my childhood paintings. "

Κ.S.

Leda Papaconstantinou

Leda Papaconstantinou (1945)

In the name of, 2007

Photograph, part of performance and video

MOMus Collections - Museum of Contemporary Art

This particular work by Leda Papaconstantinou, the honorary artist of the 1stThessaloniki Biennale, attempts a new passage, approach and emotional refamiliarization with spaces which house the memories, anticipations and the needs of the people who live in and visit them. The selection of the spaces where these programmed actions take place isn't immediately apparent. What can Omonia square, the Haftia, Votanikos and Menadrou street have in common with Stavroupolis' Simahika, Mikra, Dendropotamos and Exohi? What can the economic refugees who live and work in the neighborhoods of Greek cities have in common with the soldiers of the Western Front who were buried in the Commonwealth cemeteries of World War I, with Jews, Armenians and Thessaloniki's Protestants?

S.T.