Animus Immortalis Est

“Shoot me, cowards. You will kill a man, not my ideas.”

Che Guevara's last words sound like a hymn to the inalienable human rights he had fought for before his untimely death turned him into a symbol of the uprising against the social injustice suffered by Cuban farmers.

And it is true that, throughout history, human intolerance has often sought to eliminate the different way of thinking by killing the body that functions as the carrier and instrument of expression of this difference.

Whether it is religious beliefs or political ideologies, freedom of thought and of conscience, which should be a non-negotiable human right, is often targeted and persecuted in the context of an established order of things. Freedom, first of all individual freedom, concerning the right to the expression of a personal belief, to equality, to education, to a treatment unaffected by social or racial discrimination. And then collective freedom, especially in times of civil or occupation wars, or totalitarian regimes, which bring to the surface what may be darkest within a man, in his attempt to eliminate his ideological opponent.

Because often taking life away is not enough. Hatred against the one who resists their own ideologies, sometimes makes people turn cruelly against the ‘other’ tearing his body with rage, thus embodying in the foreign body their own internal disease. And torture or martyrdom can even become an exhibit, an apotropaic symbol of absolute supremacy.

It is this same mechanism that, transferred to the realm of the collective, characterizes the operations of extermination of entire peoples: the conquest of territories and the killing of indigenous peoples are not enough. What has to be abolished is that which constitutes the national identity of the conquered collective. And this removal of collective identity takes place through the destruction or usurpation of its cultural heritage. The uprooting of the survivors from their world thus becomes even more painful, since they are deprived of the right to what is most treasured after life itself.

But an idea can not be killed. Its light continues to burn, strengthened by the sacrifices of those who defended it at all costs. And even after the body has been destroyed, the form is raised to a symbol and it becomes a source of inspiration, to remind us that the values for which man fought and sacrificed himself are always alive, due to the immortal spiritual flame that we all hide within us.

The National Gallery-Museum of Alexandros Soutsos (EPMAS) curatorial team

Feels like home

"Give me a place to stand and I can move the Earth."

Archimedes

Home, as space that combines Place, Time and Memory, continuously interconnects people, feelings, expectations, hopes and disappointments.

Homer was the first to raise in Odyssey the concept of home with the weight of Nostos and the associations to love and devotion of family members. The image of the "rejuvenating smoke" became the par excellence timeless and universal symbol of the house as a place of return to a world of care and protection. In Plato's Phaedrus the cosmic procession of the gods of Olympus consists of Zeus leading ten gods and goddesses of Olympus through the backs of Uranus. The one that is missing is Hestia (Εστία in Greek) that never leaves her place at home. Home is always there, the center of mortal life, a symbol and guarantee of stability and protection.

From the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, writers and artists, in the light of modernity, re-examined the meaning of home and revised its traditional associations. In the climate of a general reaction to the patriarchal family of dominant capitalism, to the conservatism of social order and to the dual morality of male power, they oppose the free expression of the Ego, in pursuit of personal happiness outside the surrendered values and the subordinate.

In this context, the works included in the exhibition chapter "Feels Like Home" present images of a collective unconscious that do not necessarily come from experiences of our childhood but from what childhood itself symbolizes: innocence, safety, security of the "first home", of mother's arms. The liberating power of imagination, enhanced by memory’s charms, constitute the concept of home, either as a space or as an ideology, with all its meanings and associations.

Privacy is emphasized as an essential component of human dignity, of personal expression and freedom but also as an adversary in awe to the cruelty and indifference of public life; home is presented as an existential space, a metaphor for the human need to belong, but also the metaphysical search of our spiritual home and center.

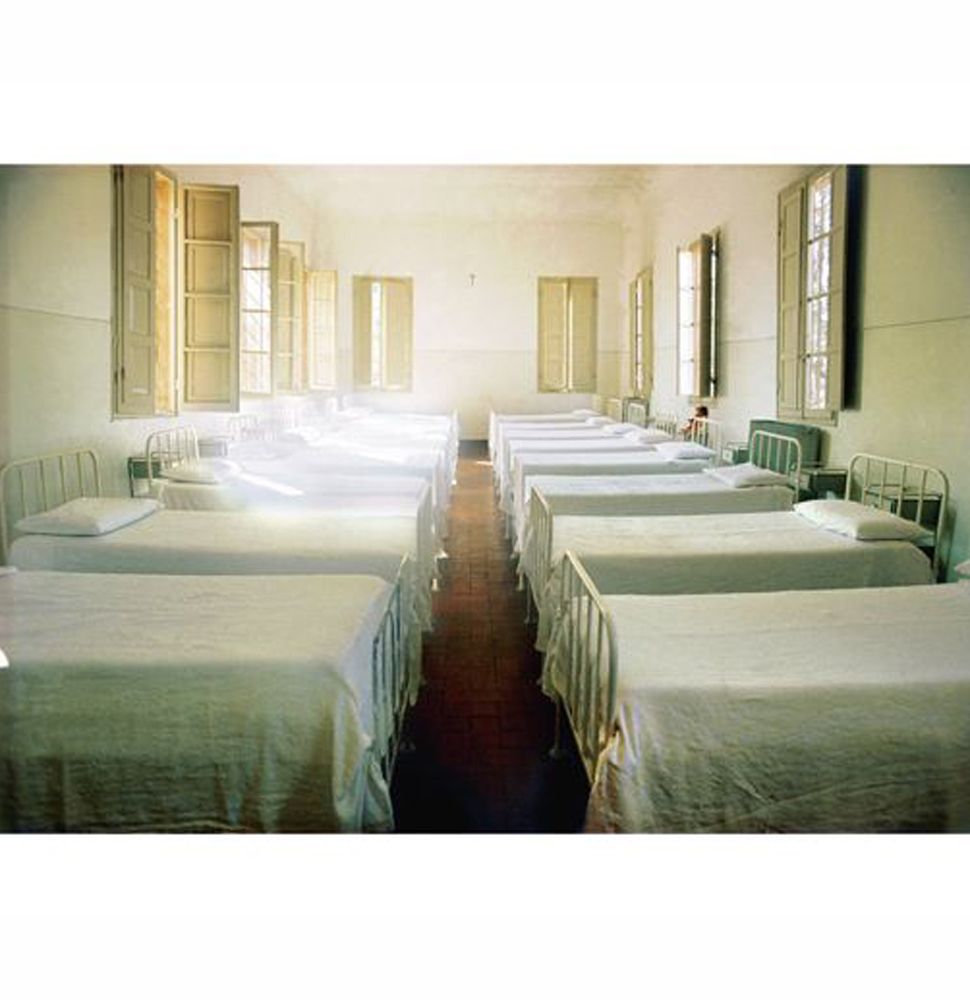

Finally, there are references to alternative case of “homes” (prisons, sanatoriums, makeshift shelters for the homeless etc.) that overturn the positive connotations of the term, without denying home’s shelter concept. Art, after all, as a contradiction to the complacent model of the leveling discourse of power, always mirrors the Other and the Elsewhere.

The National Museum of Contemporary Art (EMST) curatorial team

Climate crisis

Land and water.

A Greek phrase that since antiquity symbolizes the complete submission of one’s most valuable belongings to the conqueror. By whom has humanity been conquered and where has it been driven? What kind of reality, which causes and what phenomena "define" the complete submission of “land and water” today? How has humanity conquered earth, how has it exploited and spent its gifts?

The climate crisis is now being felt globally, and that was expected.

Earth’s memory and its traumas were made by nobody else but us, who today live in the era of the so-called "Anthropocene", experiencing humanity’s interventions and observing the irreversible consequences of our own choices.

In this chapter, each project/element is also a ghost: it is the fire that burns cities and forests, it is agriculture - the most ancient and revolutionary technology - and its natural and social dimensions, it is the remnants of our work on earth, our every passage, literally or metaphorically above the land of our existence.

The MOMus curatorial team